Beyond Commentaries: A Fresh Approach to Teaching the Book of Matthew

Written by Wes Olmstead

At our graduation weekend this past spring, one of my students introduced me to his mother, who had been in the first class I taught at Briercrest thirty-five years earlier. (I confess that it was a bit sobering to think about what she might have heard if she listened closely in that class!)

Over those many years, I’ve had the privilege, at some point, to read and think about each book in the New Testament with our students. That said, my first love is for the Gospels—what one ancient teacher called “the first fruits of all the Scriptures.” Among the Gospels, it has been Matthew’s that I have most frequently been asked to teach.

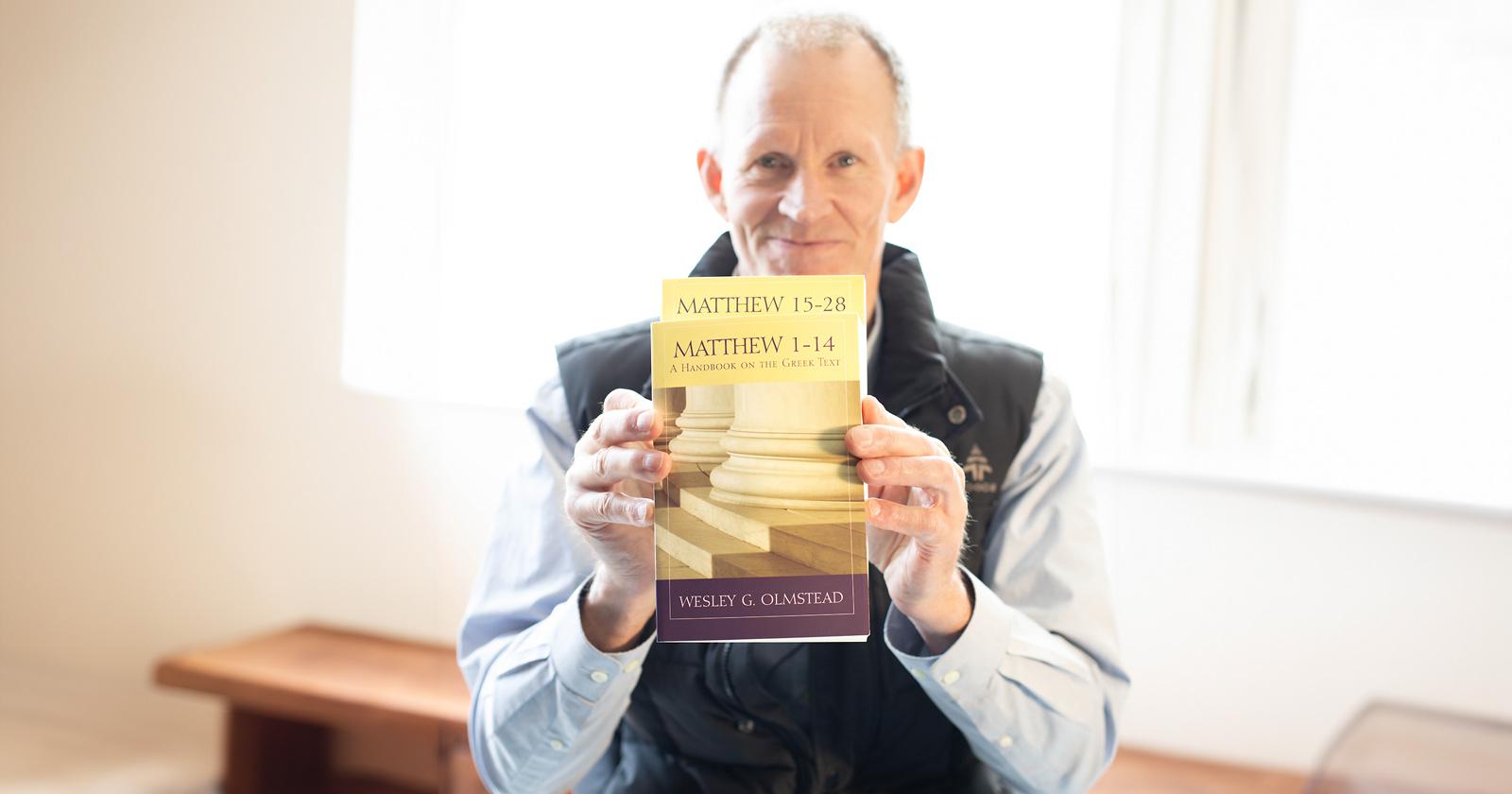

So when I was invited to contribute a two-volume work on the Gospel of Matthew to a series produced by Baylor University Press, I immediately accepted.

The books in this series are not commentaries in the ordinary sense.

Instead, they comment on each syntactical unit in the Greek New Testament. Even the best commentaries on the Greek text of the New Testament can only comment on syntax selectively. Quite often, the comments are mundane, explaining how the various parts of a given sentence are related. But, inevitably, the way we understand the relationship of these parts influences the way we hear larger wholes, and, not infrequently, what is at stake is theologically significant.

For example, does Jesus say to Peter (16:19) that “whatever you bind on earth will have been bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will have been loosed in heaven” (so, e.g., NASB, CSB) or, as I think, “whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven” (so, e.g., NRSV, NIV)?

Whatever we make of that particular question, the point is, I hope, obvious: it is impossible to listen carefully to any communication without paying attention to how it is expressed. And that means paying attention (whether consciously or not) to grammar and syntax.

I have been delighted, in the few years since the publication of these volumes, to hear from pastors and scholars who have found them helpful. But I am not without regrets—not least that I did not consult the early Greek commentators on the Gospel more consistently. That now seems like a painfully obvious oversight but one to which New Testament scholars are prone, often being more interested in the period leading up to the New Testament than its immediate aftermath.

Perhaps surprisingly, my growing interest in the patristic period (and especially in the commentary of the early Greek fathers) has coincided with my renewed interest in the way that we teach Ancient Greek.

We are, at Briercrest, in the midst of a thorough renovation of our Greek program (and of our Hebrew program, too). That ‘renovation’ probably deserves its own blog post. Still, I can, very briefly, point to two of its defining characteristics here:

- Because of the striking continuity of the Greek language across its history, our program introduces students to Greek across the eras. We want to help our students prepare to read Scriptural texts wisely while also listening carefully to the early Christian commentary on these texts and to the wisdom of the classical tradition.

- Because we want our students to learn the language and not merely to learn about it, they read extensively and write, speak, and listen to Ancient Greek in an immersive context.

Analysis is important. However, interpreters do not live by analysis alone.

You can find these works on the analysis of Matthew’s Gospel at the following links*:

*Disclaimer: The author will receive royalties at no extra cost to you if you purchase his books using the above links.